P.O. Box 80, Cooper Station

New York, NY 10276

212-673-7922

208-693-6152 fax

read an excerpt

His subject [is] the transformation of war into television event, the brainwashing of American youth into mindless killing machines, the inherent sexism of the military...Try thinking about an Iraqi soldier buried alive in sand, huddled in a fetal position 15 feet underground and treasuring his last gulp of oxygen. It's very chilling... This is an amazingly personal account of the Gulf War from the perspective of a foot soldier. The style of writing reminds me in places of Burrough�s Interzone-era prose. It drifts from realistic storytelling into stream-of-consciousness fantasy....I don�t know if James Chapman was really in the Persian Gulf, but this book has an honesty about it that makes me believe he was....quite a discovery.

The finest thing I�ve yet encountered on the television war known as the Gulf War. Protagonist V.J. is having a bad incarnation and thinks maybe a war is what he needs to get him out of a bad slump. Isn�t that what the country felt like too? Chapman�s prose shoots through an America on the eve of war, then crosses over to the killing grounds. Fear energy flickers around the edges of everything living and dead in this masterful work...The images you didn�t see on CNN are all here. An important work of the American artistic conscience. James Chapman's Glass (pray the electrons back to sand) is subtitled "A Television-War Novel," and its ostensive subject is the Gulf War of 1991. Chapman's allegiance to experimental fiction carries him far afield from the traditional "realistic" war novel. Even though Glass pays homage to certain qualities of war fiction that we are familiar with, such as boot camp degradation and the terrors of front line battle, the novel adds layers of surrealism that nearly reinvent the genre. Chapman uses techniques that are startlingly cinematic -- abrupt montage-like shifts in points-of-view and the intercutting of fantasies and delusions, not to mention television broadcasts and commercials -- which at times suggest the political aesthetics of a filmmaker like Jean-Luc Godard, whose experimental films ironically are often accused of being more akin to polemical literary essays than movies. But there should be no mistaking Chapman's achievement, which is literary in the highest sense of the word: as a war novel with elements of absurdist comedy and violent black humor, Glass is more subversive and disturbing than canonical "classics" like Catch-22 and Slaughterhouse-Five. Yet we come away from a reading of Glass feeling that Chapman has given us a "realistic" cultural critique of how our personalities become media saturated and militarized.

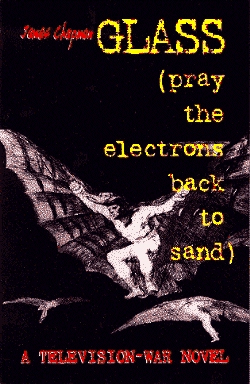

Glass (pray the electrons back to sand)

by James Chapman

$9.50 243 pp. ISBN 1-879193-02-7

This is a novel that absolutely should be read by everyone who wants to understand the experience of war and of the mind under the influence of fear....Glass is an absolutely unforgettable novel--apocalyptic, ironic, metamorphic.

--Susan Smith Nash, Taproot Reviews

--Publishers Weekly

--Kevin Goldsmith, The Unit Circle

--Logocrit

Glass is divided into four distinct sections, the first of which -- "Private" -- relates the meltdown of a 33-year-old civilian named VJ, short for Valentine Janowski: "I was trapped with a woman I didn't love, who periodically hated my ass, in a stupid matchbox house near the airbase, jets all the time screaming over, on a career plan for low-ball treadmill death, waiting out my heart attack, saving up for the mid-line coffin." Janowski's first-person account describes a ferocious two days that encompass the accidental electrocution and death of a co-worker at the television factory where VJ works, and a harrowing late-night marital scuffle that culminates in the bedsheets literally ablaze and Janowski overcome with smoke inhalation. Every aspect of his life is described in terms that suggest a war zone, with the most corrosive imagery used when talking about his marriage:

Love is the enemy within. It's the peace movement, saying negotiate, you have to coexist, hey she's your wife, look at them eyes, remember the moment by the train tracks, remember the kiss against the goddamn coffeeshop wall. Love conquers all it settles for, go ahead be a good guy and apologize if that's what she wants, you get big shot of painkiller in return. Forgive. Eat shit. A hippie leader in my brain was shunting over into a circuit called "Life Could Be Cute." It was time to kill the hippie...

Janowski is never really sober beyond the half-drunk hangovers that bring him to his job, where he usually falls asleep at his workbench. The psychological toll seems to have reached a point where he frequently dissociates via delusional-like episodes that he calls "The VJ Show": "I see myself moving, doing stuff, from outside." His perceptions are borderline psychotic at times. Watching nude female dancers in a strip club, he observes:

I forgot I wasn't watching TV...My body'd forgot it was there...The only way you knew it wasn't TV was you could smell things. The rotted-out smell of old alcohol could've been coming from anyplace, maybe me...I saw VJ: drunk, sick, sickly smile...

Chapman accomplishes several interesting feats in the opening section of the novel. Not only do we fully appreciate the bottoming out that leads VJ to the recruiting office, but we also begin to sense the underlying cultural dysfunction which produces the hostile and somewhat clueless individuals who are ripe for military indoctrination. Not that Janowski is a nitwit by any means. He seems always on the verge of a crucial awareness that might free him from self-destruction -- or military service, for that matter -- and indeed VJ's personality at the novel's end is dramatically transformed into something approaching the ashen solemnity of a Samuel Beckett character. While VJ can certainly be defined as the protagonist of "Glass," his presence becomes submerged and no longer center-stage after the novel's opening pages. The character of VJ never completely disappears from the story, but in the subsequent sections of Glass Chapman opens his authorial lens to a wider presentation of the war. We see the Gulf War filtered through other voices and perspectives, cross-cutting between the battlefield and the homefront, casual observers and angry protesters, as well as media monoliths like CNN and network television. We also see the devastation wrought upon Kuwaiti and Iraqi civilians and soldiers, whom Chapman portrays vividly in plaintive vignettes. All of this is masterfully rendered in what literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin called "heteroglossia" -- a multi-voiced style that displays the world for us in all its energetic clashes of cultures and ideologies.

Chapman's evocation of boot camp in the novel's second section, "Clear Channel," is a tour-de-force of grotesque and surreal imagery:

...there's booths with bake sale goodies, manned by nice young women in cotton lawn-party dresses, they're smiling and nodding at the recruits, showing off these baked things in heavy glass boxes. Jesus-on-the-cross cookies, where His face is iced white and brown jimmies for hair; bowls of, looks like, blood whipped in a blender froth borscht-pink, served in dixie cups, skin shreds floating dark as beets; what appears human shit dipped in chocolate and stuck on a stick; plus aluminum trays of white entrails tangled in blue-cheese crumbles; and cubes of some kind of black jello.

Janowksi's military indoctrination involves a series of humiliations designed to turn his already well-defined sexual hostility into an authentic killer's instinct. In one of the novel's most powerfully shocking scenes VJ is taunted and verbally emasculated by a woman "judge" until he explodes in rage and kills her with a broken glass bottle, then literally scalps the corpse. After which, he is roundly congratulated by his military brethren, "VJ, babe, ya made it." Chapman's point is brutally clear: military training zeroes in on the worst of our violent social sicknesses and reinforces them until we are sufficiently prepared to "do battle" with whomever the military designates as our "enemy."

The final two sections of Glass -- "Air War" and "Dead Air" -- represent the novel's finest accomplishment in threading VJ's battle experiences through a panoramic montage of Gulf War perspectives. Chapman's control and breadth of vision are especially remarkable because he has succeeded in expressing an experimental literary impulse without forfeiting the violent naturalism that traditionally propels war fiction. The novel's "story" never loses momentum or direction, every vignette and aside is meaningful within the novel's overall design. The text is increasingly more fragmented, but every fragment adds force to Chapman's portrait of the debilitating collective unconscious that breeds warfare and social injustice:

In West Texas, a guy on a Harley is trying to taunt a farm boy into fighting. The biker's making laughing roar sounds. The farm boy forgets how to talk.

The farm boy's father has a paper from a psychiatrist that says he's unemployable cause he's all the time depressed.

The Harley guy's father's head was shot off in Vietnam. He's got his father's neck.

The style in which Chapman has chosen to write Glass is an acknowledgment that the Gulf War was unlike other wars in our history. Soldiers, civilians, protesters and politicians alike were mystified -- and still are today -- as to what in fact the fighting and killing were really about. Glass exposes a darkness within the American character that suggests we carry warfare within us at all times, ever ready to be encouraged and unleashed. Chapman is equally effective at showing us how the Gulf War was kept sanitized for us by an unknowingly complicit news media that were just as dazzled as the military by the new technologies that enhanced the efficiency of both the killing and the reporting. As one of VJ's marine buddies remarks, "We made our country so cool that we can even have a war be like a movie if we want."

...[Glass has] broken through to a hard-edged art that asks us to be mindfully deranged, thoughtfully unhinged, to live and communicate on a suicidal edge that refuses suicide, that denounces death as just one more meaningless "meaning," one more unnecessary charade. Chapman [has] a clarity of purpose that rejects cynicism and irony -- literary options which seem evermore like outmoded artifacts of an exhausted age -- and replaces them with a brutal honesty, imploring us as readers to alter our lives by stripping away every mask and obstacle standing between what we do and what we are capable of.

--Bob Wake, Cambridge Book Review.